Creature From the Black Lagoon Turn Off Family Mode

In 1818, Mary Shelley created popular culture's showtime and most enduring monster in "Frankenstein; or, The Mod Prometheus." Since then, "women accept ever been the most important function of monster movies," equally Mallory O'Meara states in "The Lady From the Black Lagoon," her engaging and compelling, if uneven, book about artist Milicent Patrick, the unsung designer of another iconic monster.

As a teenager, indie horror filmmaker O'Meara became absorbed by Universal Pictures' 1954 "Animate being From the Black Lagoon." Its eponymous amphibian star — a scaled, humanoid figure fondly known to generations of sci-fi geeks as the Gill-man — was the concluding of Universal'south classic monsters, joining the studio's pantheon alongside Dracula, the Frankenstein monster and his Helpmate, and the Wolfman, among others. The Gill-man was besides, as O'Meara learned to her delighted amazement, the first — and at the time, only — pic monster to accept been designed by a woman.

Yet as she researches her new artistic beat out, O'Meara'due south delight swiftly turns to bewilderment and acrimony.

Patrick's design for the creature had for decades been credited to Universal makeup artist Bud Westmore, who fired her rather than take her role in its success become known. "Milicent's incredible life should have earned her an honored place in flick history," O'Meara fumes, and with practiced reason. "But few even recognize her name." "The Lady From the Black Lagoon" sets out to right that incorrect, every bit O'Meara goes in search of this mostly unknown, if perhaps ultimately unknowable, artist.

(Silver Screen Collection / Getty Images)

Born Mildred Elizabeth Fulvia di Rossi in 1915, the adult female — who later became Milicent Patrick — was the heart kid of three. When she was half dozen, her father, Camille Charles Rossi, a structural engineer, was hired to piece of work on William Randolph Hearst'south vast California Central Coast retreat, La Cuesta Encantada, better known as Hearst Castle. Rossi soon became the project's construction superintendent, reporting to Julia Morgan, California's first licensed woman builder and the castle'due south designer.

Like other children whose parents labored there, Mildred often visited this dreamland, with its two,000-acre private zoo and constantly shifting human menagerie of celebrity guests. Just her father seems to have navigated Hearst's kingdom uneasily, fighting nonstop with Morgan, and was dismissed subsequently a decade. In her diary, Morgan chosen him "unduly revengeful," and the superintendent of Hearst's ranch said that Rossi "seemed to glory in human misery." He was, perhaps, the first monster in his girl's life.

A gifted artist, Mildred received three scholarships to Chouinard Art Establish, which served every bit an artist/animator incubator for nearby Walt Disney Studios. The schoolhouse after became CalArts. In early on 1939, she was tapped to work for Disney's storied ink and pigment department.

Staffed entirely past women, it was housed in a split edifice on the Disney studio campus, where the so-called Ink and Pigment Girls reproduced tens of thousands of animators' drawings onto celluloid, a mind-bogglingly laborious process. As Patricia Zohn wrote in a 2010 Vanity Fair article, "their task was to make what the men did wait good … at an average of viii to 10 cels an hour, 100 girls could but, in theory, turn out less than one minute of screen time by the end of the twenty-four hour period." At Disney, Mildred worked as a color animator (and then considered a special furnishings technique) on "Fantasia," contributing to iv sequences, including the legendary "Night on Baldheaded Mountain," where she created gorgeous colour pastel blitheness for the demonic Chernabog — "the virtually magical Disney graphic symbol" for O'Meara and generations of monster lovers.

Mildred left Disney in the wake of the 1941 animators' walkout, a strike that irrevocably changed the manner the studio functioned. But Mildred wasn't among the strikers. At some betoken, she had embarked upon an affair with another Disney animator, Paul Fitzpatrick. His meaning wife found out and killed herself and their unborn child. The tragedy left Mildred and Fitzpatrick complimentary to marry, and as well estranged Mildred from her family. When, after a few years, she and Fitzpatrick divorced, she took on the name Mil Patrick. At some betoken she refined this to Milicent Patrick. She claimed to be Disney'south first female animator — probably not true, but close plenty — and further embroidered her background by proverb she was an Italian baroness.

Milicent Patrick, the discipline of Mallory O'Meara'southward volume, "The Lady From the Blackness Lagoon."

(From the author's personal drove)

She certainly looked the role, every bit one can come across in a promotional film and photos from her time at Disney — strikingly beautiful, with long blackness pilus and a regal air that not even Ink and Paint's utilitarian smocks could diminish. She continued to create art, including illustrations for a collection of off-color jokes, but mostly seems to have worked as a model.

And so, in 1947, she met William Hawks, brother of filmmaker Howard Hawks and also a producer. She began to get uncredited bit parts every bit an actress — water nymph, flashy woman, tavern wench — in more often than not forgettable films. She became involved with actor Frank Fifty. Graham, all-time known for voicing the lascivious Wolf in Tex Avery's cartoon short "Red Hot Riding Hood." A few months into their relationship, in September 1950, Graham committed suicide. His will independent a note that read, "To Mildred, I leave nothing except the pleasance she volition take knowing that now she won't have to make up one's mind whether I am good plenty for her or not." Also, a postscript: "Gee, I wish Mildred had chosen me dorsum yesterday morn."

By this point — most halfway through O'Meara'due south volume — readers may be thinking, "Gee, I wish nosotros'd become to the Animal."

(Ken Rohrer)

This is the center of O'Meara's story, and information technology'southward a good, if infuriating, 1. O'Meara writes that, in 1952, while working equally an actress on the Universal lot, Patrick met the head of the studio'southward makeup department, Bud Westmore. (I recently came across a 1948 publicity photo online of Patrick holding the monster's mask from the film from the same twelvemonth "Abbott and Costello Encounter Frankenstein," with a handwritten note saying that she helped make the mask and likewise did its fine detail painting.) Westmore oversaw makeup for that before picture show, so it's possible that Patrick met him at that time, and that Westmore was already familiar with her piece of work when, in 1952, she was hired as makeup designer for the B moving-picture show that became "Brute From the Black Lagoon."

Unfortunately, none of her preliminary or finished sketches seemed to survive.

(Family Collection)

But others familiar with the movie (including Chris Mueller, who sculpted the Gill-human's mask) land unequivocally that Patrick designed the animate being, a svelte, elegant and surprisingly sexy monster whose influence extends to Guillermo del Toro'due south 2017 Oscar-winning homage, "The Shape of Water." During previews, it became clear that Universal's new monster flick was going to be a hitting, its audience reactions fueled, no doubt, by an underwater pas de deux between the Gill-man and his female, human casualty that still retains an erotic charge. The studio decided to capitalize on Patrick'due south involvement and transport her on a publicity tour with the tagline, "The Beauty Who Created the Creature."

Westmore, known to be difficult and decision-making with underlings, hit the roof.

O'Meara summarizes memos from the publicity team (they tin be read in Tom Weaver'southward in-depth "The Creature Chronicles," 1 of O'Meara's sources) detailing their battles with the makeup main. The consequence: Patrick was sent out with masks of several Universal monsters, including the Brute, and was renamed "The Dazzler Who Lives With the Beasts." Even this wasn't plenty for Westmore. He struck Patrick's name from the credits, replaced it with his ain and, when she returned from her successful, near monthlong bout, had her fired.

At one indicate, O'Meara rages, "Several [people] expressed doubt that [Patrick's] story could exist more than an commodity, let solitary fill an entire book." The truth is, much of the book is padding, and it oft reads equally though it were written for a immature audience, with long passages and footnotes explaining who Hearst was, what a scream queen is, and and so on.

If Patrick left any diaries, journals, letters or the like, they're not quoted from here, though O'Meara does speak with others intrigued by her history (including Mindy Johnson, whose 2017 "Ink & Pigment: The Women of Walt Disney'southward Animation," delves deeply into the part of women in the studio'due south early years).

But many specific details of her life equally a working artist remain deficient.

(Allan Amato)

O'Meara even visits the artist's niece, who talks to her for hours about her aunt, and gives the writer access to Tupperware filled with Patrick's papers and ephemera. "The answers to almost all of my questions well-nigh Milicent were in these boxes," O'Meara states, just she shares nothing of what she learns, except in the vaguest terms.

We larn that Patrick is "a friendly and warm person," with "a warm personality," "well-spoken, friendly and charming." "Socializing was easy for Milicent," and Graham's suicide "caused her to lean harder than ever on her friends." There are no interviews with friends, and no citations for quotes, including comments similar "[Milicent] loved looking glamorous. Information technology made her happy" or, "How marvelous that she refused to try to fit into the male child's club [sic], that she was unapologetically herself," or, afterward, that she was "aggress by loneliness."

O'Meara, unsurprisingly, identifies with her discipline. Like Patrick and many other women, O'Meara has her own experiences of being harassed, abused and treated contemptuously past men in the moving-picture show industry. Withal, her book could use less of the author'southward own rage and occasional fangirl gushing, even so well deserved, and more about its subject, a woman whose male parent was said to "glory in human misery," who knew firsthand the devastating upshot of suicide, and who submitted a memo totting up the harm to her wardrobe for the Universal bout (amounting to nearly $iv,000 in today'southward coin).

"One cocktail clothes—completely ruined.

One cocktail clothes—beading cleaved and lost.

Ane gabardine suit—shrunk and can't be repaired.

One lace coat—burned, torn, and shrunk—ruined beyond repair.

I afternoon dress—torn but repairable.

One pair of earrings—cutting in half past pub. man and stones lost.

One velvet blouse—torn, tin can be repaired."

All of which makes one wonder if Patrick was accompanied on tour non just past masks simply past the monsters themselves.

(Erin Craig / Hanover Square Printing)

"Women are the almost of import office of horror because, by and large, women are the ones the horror happens to," O'Meara writes.

"Women take to endure it, fight it, survive it — in the movies and in real life. Horror films assistance explore these fears and imagine what information technology would be similar to conquer them. Women demand to see themselves fighting monsters. That'south role of how we effigy out our stories. Merely we also need to see ourselves backside-the-scenes, creating and writing and directing. Nosotros demand to tell our stories, too."

Patrick died in 1998, at age 82, largely forgotten except for a coterie of devoted fans. O'Meara has seen to it that she won't be forgotten again. Her book is a tearing and oft very funny guide to the distaff side of geekdom and reproduces photos and examples of Patrick's piece of work, many previously unpublished. That alone would be worth the price of admission to the earth of this circuitous, brilliant artist.

::

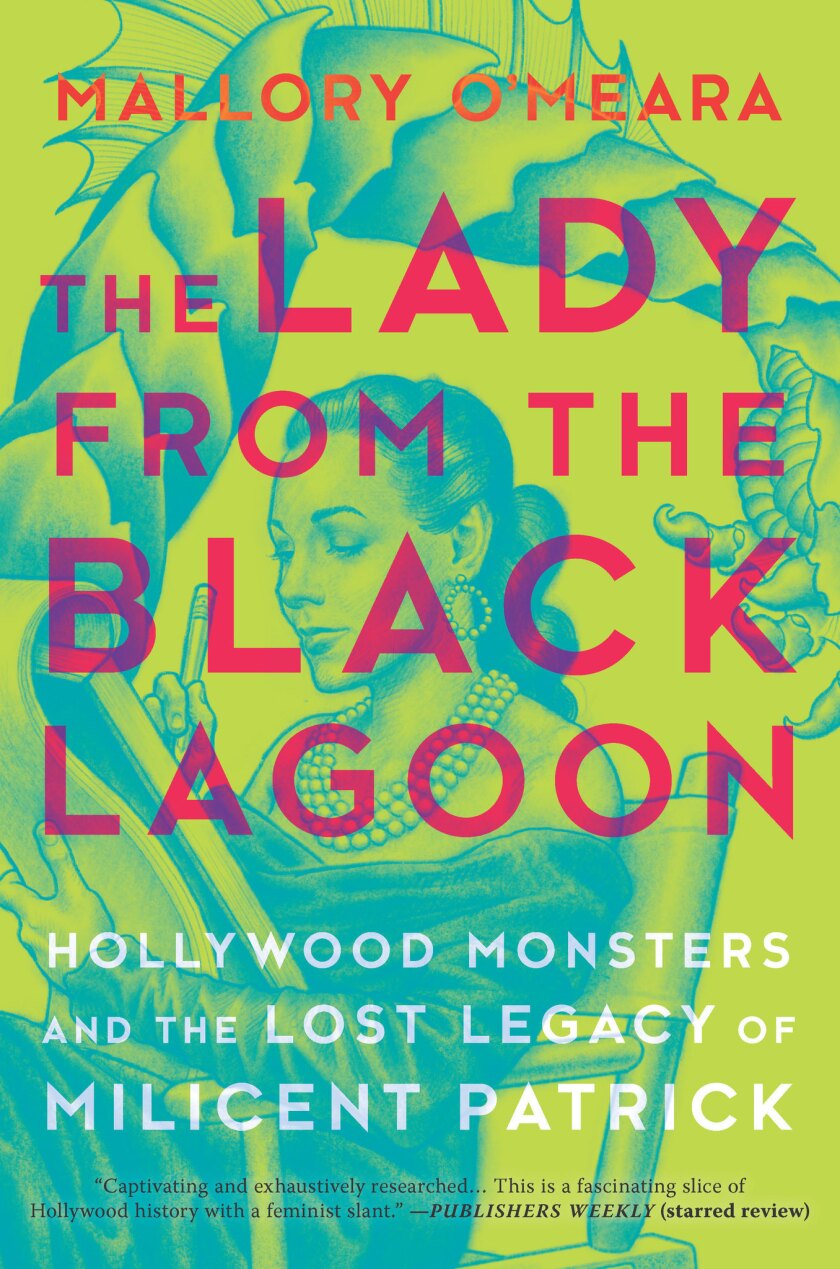

"The Lady From the Black Lagoon: Hollywood Monsters and the Lost Legacy of Milicent Patrick"

Mallory O'Meara

Hanover Square Printing, 351 pp, $26.99

Mitt's novel, "Curious Toys," will be published this autumn.

Source: https://www.latimes.com/books/la-ca-jc-lady-from-the-black-lagoon-review-20190301-story.html

0 Response to "Creature From the Black Lagoon Turn Off Family Mode"

Post a Comment