what percent of americans are registered to vote

The historical trends in voter turnout in the United States presidential elections have been determined past the gradual expansion of voting rights from the initial brake to white male property owners anile 21 or older in the early on years of the state'due south independence to all citizens aged eighteen or older in the mid-20th century. Voter turnout in Usa presidential elections has historically been higher than the turnout for midterm elections.[i]

Approximately 240 meg people were eligible to vote in the 2020 presidential ballot and roughly 66.1% of them submitted ballots, totaling almost 158 million. Biden received about 81 million votes, Trump nigh 74 one thousand thousand votes, and other candidates (including Jo Jorgensen and Howie Hawkins) a combined approximately 3 1000000 votes.

History of voter turnout [edit]

U.S. presidential election popular vote totals as a percentage of the total U.South. population. The blackness line is the total turnout, while colored lines reflect votes for major parties. This nautical chart represents the number of votes cast as a percentage of the total population, and does not compare either of those quantities with the percentage of the population that was eligible to vote.[3]

Early 19th century: Universal white male suffrage [edit]

The gradual expansion of the right to vote from only property-owning men to include all white men over 21 was an important movement in the menses from 1800 to 1830.[iv] Older states with holding restrictions dropped them, namely all but Rhode Island, Virginia and N Carolina by the mid-1820s. No new states had property qualifications, although three had adopted tax-paying qualifications – Ohio, Louisiana and Mississippi, of which only in Louisiana were these pregnant and long-lasting.[v] The process was peaceful and widely supported, except in Rhode Island. In Rhode Isle, the Dorr Rebellion of the 1840s demonstrated that the demand for equal suffrage was broad and strong, although the subsequent reform included a significant property requirement for any resident born exterior of the United states of america. However, costless blackness men lost voting rights in several states during this period.[6]

The fact that a human being was now legally immune to vote did not necessarily mean he routinely voted. He had to exist pulled to the polls, which became the most of import role of the local parties. These parties systematically sought out potential voters and brought them to the polls. Voter turnout soared during the 1830s, reaching about fourscore% of the adult male population in the 1840 presidential ballot.[7] Tax-paying qualifications remained in only five states by 1860 – Massachusetts, Rhode Isle, Pennsylvania, Delaware and North Carolina.[8]

Another innovative strategy for increasing voter participation and input followed. Prior to the presidential election of 1832, the Anti-Masonic Party conducted the nation's beginning presidential nominating convention. Held in Baltimore, Maryland, September 26–28, 1831, information technology transformed the process by which political parties select their presidential and vice-presidential candidates.[9]

1870s: African American male person suffrage [edit]

The passage of the Fifteenth Subpoena to the United States Constitution in 1870 gave African American men the correct to vote. While this historic expansion of rights resulted in significant increases in the eligible voting population and may take contributed to the increases in the proportion of votes cast for president as a percentage of the full population during the 1870s, at that place does not seem to have been a significant long-term increase in the percentage of eligible voters who plough out for the poll. The disenfranchisement of most African Americans and many poor whites in the South during the years 1890–1910 likely contributed to the decline in overall voter turnout percentages during those years visible in the chart below.

Early 1920s: Women'due south suffrage [edit]

There was no systematic collection of voter turnout data by gender at a national level before 1964, but smaller local studies indicate a low turnout among female person voters in the years following Women'south suffrage in the United States. For example, a 1924 study of voter turnout in Chicago found that "female Chicagoans were far less likely to have visited the polls on Election Twenty-four hour period than were men in both the 1920 presidential election (46% vs. 75%) and the 1923 mayoral competition (35% vs. 63%)."[ten] The study compared reasons given by male person and female non-voters and plant that female non-voters were more than likely to cite general indifference to politics and ignorance or timidity regarding elections than male person not-voters, and that female voter were less likely to cite fright of loss of business organisation or wages. Virtually significantly, however, xi% of female non-voters in the survey cited a "Atheism in woman'southward voting" every bit the reason they did non vote.

The graph of voter turnout percentages shows a dramatic pass up in turnout over the first two decades of the twentieth century, ending in 1920 when the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution granted women the right to vote across the U.s.. But in the preceding decades, several states had passed laws supporting women's suffrage. Women were granted the right to vote in Wyoming in 1869, before the territory had become a total state in the union. In 1889, when the Wyoming constitution was drafted in grooming for statehood, it included women'due south suffrage. Thus Wyoming was also the first total state to grant women the right to vote. In 1893, Colorado was the offset state to amend an existing constitution in order to grant women the right to vote, and several other states followed, including Utah and Idaho in 1896, Washington State in 1910, California in 1911, Oregon, Kansas, and Arizona in 1912, Alaska and Illinois in 1913, Montana and Nevada in 1914, New York in 1917; Michigan, South Dakota, and Oklahoma in 1918. Each of these suffrage laws expanded the body of eligible voters, and because women were less likely to vote than men, each of these expansions created a pass up in voter turnout rates, culminating with the extremely low turnouts in the 1920 and 1924 elections later the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment.

This voting gender gap waned throughout the middle decades of the twentieth century.

Historic period, pedagogy, and income [edit]

Voter turnout by sex and age for the 2008 U.South. Presidential Election.

Age, income, and educational attainment are significant factors affecting voter turnout. Educational attainment is perhaps the best predictor of voter turnout, and in the 2008 election, those holding advanced degrees were iii times more than probable to vote than those with less than high school education. Income correlated well with the likelihood of voting as well. The income correlation may exist because of a correlation between income and educational attainment, rather than a direct effect of income.[ commendation needed ]

Age [edit]

The age difference is associated with youth voter turnout. Some argue that "age is an important factor in understanding voting blocs and differences" on various issues.[11] Others argue that young people are typically "plagued" by political apathy and thus do not have strong political opinions.[12] As strong political opinions may be considered one of the reasons behind voting,[13] political apathy amid young people is arguably a predictor for low voter turnout. One study found that potential young voters are more willing to commit to voting when they see pictures of younger candidates running for elections/office or voting for other candidates, surmising that young Americans are "voting at higher and similar rates to other Americans when there is a candidate under the age of 35 years running".[fourteen] Every bit such, since most candidates running for office are pervasively over the age of 35 years,[15] youth may not be actively voting in these elections because of a lack of representation or visibility in the political process.

Recent decades have seen increasing business organisation over the fact that youth voter turnout is consistently lower than turnout among older generations. Several programs to increase the rates of voting among young people – such as MTV'south "Rock the Vote" (founded in 1990) and the "Vote or Die" initiative (starting in 2004) – may take marginally increased turnouts of those between the ages of 18 and 25 to vote. However, the Stanford Social Innovation Review found no prove of a decline in youth voter turnout. In fact, they argue that "Millennials are turning out at similar rates to the previous two generations when they face their outset elections."[16]

Pedagogy [edit]

Rates in voting in the 2008 U.Southward. Presidential Ballot past educational attainment

Educational activity is some other factor considered to accept a major impact on voter turnout rates. A written report by Burman investigated the relationship between formal education levels and voter turnout.[17] This study demonstrated the upshot of ascension enrollment in college didactics circa 1980s, which resulted in an increase in voter turnout. However, "this was not true for political noesis";[17] a rise in instruction levels did not have any impact in identifying those with political knowledge (a signifier of civic engagement) until the 1980s ballot, when college education became a distinguishing gene in identifying civic participation. This article poses a multifaceted perspective on the effect of education levels on voter turnout. Based on this article, one may surmise that education has go a more powerful predictor of civic participation, discriminating more between voters and non-voters. However, this was not true for political knowledge; educational activity levels were not a signifier of political knowledge. Gallego (2010) also contends that voter turnout tends to be higher in localities where voting mechanisms have been established and are easy to operate – i.e. voter turnout and participation tends to be high in instances where registration has been initiated by the state and the number of electoral parties is pocket-sized. Ane may fence that ease of access – and non educational activity level – may be an indicator of voting behavior. Presumably larger, more than urban cities will accept greater budgets/resource/infrastructure dedicated to elections, which is why youth may have higher turnout rates in those cities versus more rural areas. Though youth in larger (read: urban) cities tend to be more educated than those in rural areas (Marcus & Krupnick, 2017), perhaps there is an external variable (i.e. ballot infrastructure) at play. Smith and Tolbert's (2005) research reiterates that the presence of ballot initiatives and portals inside a state have a positive effect on voter turnout. Another correlated finding in his written report (Snyder, 2011) was that instruction is less important as a predictor of voter turnout in states than tend to spend more than on didactics. Moreover, Snyder's (2011) research suggests that students are more probable to vote than not-students. It may be surmised that an increase of state investment in electoral infrastructure facilitates and instruction policy and programs results in increase voter turnout among youth.

Income [edit]

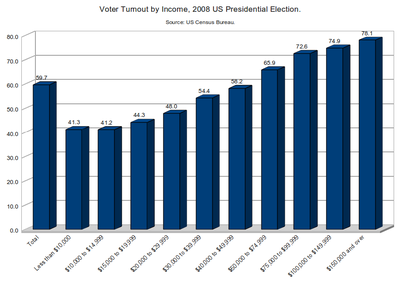

Rates of voting in the 2008 U.S. Presidential Election by income

Wealthier people tend to vote at higher rates. Harder and Krosnick (2008) debate that some of the reasons for this may be due to "differences in motivation or power (sometimes both)" (Harder and Krosnick, 2008), or that less wealthy people take less energy, time, or resources to allot towards voting. Another potential reason may be that wealthier people believe that they have more at stake if they don't vote than those with less resources or income. Maslow'south bureaucracy of needs might also help explain this hypothesis from a psychological perspective. If those with low income are struggling to meet the basic survival needs of food, h2o, safe, etc., they volition non be motivated enough to reach the concluding stages of "Esteem" or "Self-actualization" needs (Maslow, 1943) – which consist of the desire for dignity, respect, prestige and realizing personal potential, respectively.

Gender gap [edit]

Since 1980, the voting gender gap has completely reversed, with a higher proportion of women voting than men in each of the final nine presidential elections. The Center for American Women and Politics summarizes how this trend can be measured differently both in terms of proportion of voters to not-voters, and in terms of the bulk number of votes cast. "In every presidential ballot since 1980, the proportion of eligible female adults who voted has exceeded the proportion of eligible male person adults who voted [...]. In all presidential elections prior to 1980, the voter turnout rate for women was lower than the rate for men. The number of female voters has exceeded the number of male voters in every presidential election since 1964..."[18] This gender gap has been a determining factor in several recent presidential elections, every bit women have been consistently most xv% more likely to back up the candidate of the Democratic Party than the Republican candidate in each election since 1996.[19]

Race and ethnicity [edit]

Voter turnout in the 2008 U.S. Presidential Election by race/ethnicity.

Race and ethnicity has had an issue on voter turnout in recent years, with information from recent elections such equally 2008 showing much lower turnout among people identifying as Hispanic or Asian ethnicity than other voters (see nautical chart to the correct). One cistron impacting voter turnout of African Americans is that, as of the 2000 election, 13% of African American males are reportedly ineligible to vote nationwide because of a prior felony conviction; in certain states – Florida, Alabama, and Mississippi – disenfranchisement rates for African American males in the 2000 election were around 30%.[twenty]

Other eligibility factors [edit]

Some other factor influencing statistics on voter turnout is the pct of the country'south voting-age population[ clarification needed ] who are ineligible to vote due to non-citizen status or prior felony convictions. In a 2001 article in the American Political Science Review, Michael P. McDonald and Samuel Popkin argued, that at least in the Us, voter turnout since 1972 has not actually declined when calculated for those eligible to vote, what they term the voting-eligible population.[21] [ clarification needed ] In 1972, noncitizens and ineligible felons (depending on land law) constituted almost 2% of the voting-age population. By 2004, ineligible voters constituted nearly ten%.[22] Ineligible voters are not evenly distributed across the country, roughly 15% of California'south voting-age population is ineligible to vote – which confounds comparisons of states.[23]

Turnout statistics [edit]

The following table shows the available data on turnout for the voting-historic period population (VAP) and voting-eligible population (VEP) since 1936.[24]

| Election | Voting-age Population (VAP)[25] | Voting-eligible Population (VEP)[25] | Turnout[25] | % Turnout of VAP[25] [ clarification needed ] | % Turnout of VEP[25] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1932 | 75,768,000 | 39,817,000 | 52.6% | ||

| 1936 | 80,174,000 | 45,647,000 | 56.nine% | ||

| 1940 | 84,728,000 | 49,815,000 | 58.viii% | ||

| 1944 | 85,654,000 | 48,026,000 | 56.ane% | ||

| 1948 | 95,573,000 | 48,834,000 | 51.i% | ||

| 1952 | 99,929,000 | 61,552,000 | 61.6% | ||

| 1956 | 104,515,000 | 62,027,000 | 59.3% | ||

| 1960 | 109,672,000 | 68,836,000 | 62.viii% | ||

| 1964 | 114,090,000 | lxx,098,000 | 61.iv% | ||

| 1968 | 120,285,000 | 73,027,000 | 60.seven% | ||

| 1972 | 140,777,000 | 77,625,000 | 55.1% | ||

| 1976 | 152,308,000 | 81,603,000 | 53.6% | ||

| 1980 | 163,945,000 | 159,635,102 | 86,497,000 | 52.eight% | 54.2% |

| 1984 | 173,995,000 | 167,701,904 | 92,655,000 | 53.3% | 55.ii% |

| 1988 | 181,956,000 | 173,579,281 | 91,587,000 | fifty.3% | 52.8% |

| 1992 | 189,493,000 | 179,655,523 | 104,600,000 | 55.2% | 58.ii% |

| 1996 | 196,789,000 | 186,347,044 | 96,390,000 | 49.0% | 51.7% |

| 2000 | 209,787,000 | 194,331,436 | 105,594,000 | 50.3% | 54.three% |

| 2004 | 219,553,000 | 203,483,455 | 122,349,000 | 55.7% | 60.i% |

| 2008 | 229,945,000 | 213,313,508 | 131,407,000 | 57.1% | 62.v% |

| 2012 | 235,248,000 | 222,474,111 | 129,235,000 | 53.8% | 58.0% |

| 2016 | 249,422,000 | 230,931,921 | 136,669,276 | 54.eight% | 59.ii% |

| 2020[23] | 257,605,088 | 239,247,182 | 159,690,457 | 62.0% | 66.nine% |

Note: The Bipartisan Policy Center has stated that turnout for 2012 was 57.5 pct of the voting-age population (VAP),[ clarification needed ] which they claim was a decline from 2008. They estimate that every bit a percent of eligible voters, turnout was: 2000, 54.ii%; in 2004 60.4%; 2008 62.3%; and 2012 57.5%.[26]

The BPC 2012 vote count is depression because their certificate was written just after the 2012 election, before final counts were in. Their voting-eligible population (VEP)[ clarification needed ] does not include adjustments for felons (run across p.13). The United States Elections Project, by Michael McDonald calculates VEP including citizenship and adjustments for felons. The site's data on turnout every bit per centum of eligible voters (VEP), is slightly college and similar to BPC: 2000 55.iii%, 2004 60.seven%, 2008 62.2%, 2012 58.half dozen%. McDonald'due south voter turnout data for 2016 is 60.i% and 50% for 2018.[27]

Later analysis past the Academy of California, Santa Barbara'due south American Presidency Project institute that there were 235,248,000 people of voting age in the U.s. in the 2012 ballot, resulting in 2012 voting age population (VAP) turnout of 54.ix%.[28] The full increase in VAP between 2008 and 2012 (5,300,000) was the smallest increment since 1964, bucking the mod average of 8,000,000–13,000,000 per bike.

Run across also [edit]

- Voter turnout

- Voter registration in the United States

References [edit]

- ^ New York Times Editorial Lath (Nov 11, 2014). "Opinion | The Worst Voter Turnout in 72 Years". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- ^ "Voter Turnout By State 2021". worldpopulationreview.com . Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- ^ See "National Turnout Rates, 1787-2018" (U.s. Election Project)

- ^ Keyssar, The Right to Vote: The Contested History of Democracy in the United States (2009) ch ii

- ^ Engerman, pp. 8–ix

- ^ Murrin, John M.; Johnson, Paul East.; McPherson, James M.; Fahs, Alice; Gerstle, Gary (2012). Liberty, Equality, Power: A History of the American People (6th ed.). Wadsworth, Cengage Learning. p. 296. ISBN978-0-495-90499-ane.

- ^ William G. Shade, "The Second Party Organization". in Paul Kleppner, et al. Development of American Electoral Systems (1983) pp. 77–111

- ^ Engerman, p. 35. Table 1

- ^ William Preston Vaughn, The Anti-Masonic Party in the United States: 1826–1843 (2009)

- ^ Allen, Jodie T. (March 18, 2009). "Reluctant Suffragettes: When Women Questioned Their Right to Vote". Pew Enquiry Heart . Retrieved Jan 29, 2018.

- ^ Berman; Johnson (2000). "Historic period, appetite, and the local lease: a study in voting beliefs".

- ^ Catapano, Tyler (2014). "?".

- ^ Munsey (2008). "Why We Wrote: Why practise we vote?". APA Monitor. 39 (six): lx.

- ^ Pomante; Schraufnagel (2014). "Candidate Age and Youth Voter Turnout". American Politics Research. 43 (iii): 479–503. doi:10.1177/1532673x14554829. S2CID 156019567.

- ^ Struyk (2017). "The Autonomous Party has an age problem". CNN.

- ^ Kiesa, Abby; Levine, Peter (March 21, 2016). "Do Nosotros Actually Want College Youth Voter Turnout?". Stanford Social Innovation Review . Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- ^ a b Burden, B. (2009). "The dynamic effects of education on voter turnout". Electoral Studies. 28 (4): 540–549. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2009.05.027.

- ^ "Gender Differences in Voter Turnout" (PDF). Rutgers University Center for American Women and Politics. July 20, 2017. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- ^ Waldman, Paul (March 17, 2016). "Opinion | Why the 2016 election may produce the largest gender gap in history". Washington Mail service . Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- ^ Written report: Non-Voting Felons Increasing, ABC News, January 6, 2006.

- ^ McDonald, Michael P.; Popkin, Samuel L. (December 2001). "The Myth of the Vanishing Voter". The American Political Science Review. 95 (4): 963–974. doi:ten.1017/S0003055400400134. JSTOR 3117725. S2CID 141727274.

- ^ "2004G - United States Elections Project". www.electproject.org . Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- ^ a b "2020g - United states Elections Project". www.electproject.org . Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- ^ "Denominator - United States Elections Projection".

- ^ a b c d eastward "Voter Turnout in Presidential Elections | The American PresidencyProject". world wide web.presidency.ucsb.edu . Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- ^ "2012 Ballot Turnout Dips Below 2008 and 2004 Levels: Number Of Eligible Voters Increases By Eight 1000000, 5 One thousand thousand Fewer Votes Bandage" (PDF). Bipartisan Policy Center. November viii, 2012. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- ^ "Voter Turnout Data - United states of america Elections Project". www.electproject.org . Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- ^ "Voter Turnout in Presidential Elections". UC Santa Barbara American Presidency Project . Retrieved January 29, 2018.

Further reading [edit]

- Berman, D. and Johnson, R. (2000). Age, ambition, and the local charter: a study in voting behavior. The Social Science Journal, 37(1), pp. 19–26.

- Burden, Barry C. (2009). "The dynamic effects of educational activity on voter turnout". Electoral Studies. 28 (iv): 540–549. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2009.05.027.

- Gallego, A. (2010). Understanding unequal turnout: Education and voting in comparative perspective. Electoral Studies, 29(two), pp. 239–248.

- Gershman, C. (2018). Democracy and Democracies in Crunch. Retrieved from [one][usurped!]; likewise at https://isnblog.ethz.ch/politics/democracy-and-democracies-in-crisis

- Harder, J. and Krosnick, J. (2008). Why Do People Vote? A Psychological Assay of the Causes of Voter Turnout. Periodical of Social Bug, 64(3), pp. 525–549.

- Marcus, J., & Krupnick, M. (2017). The Rural Higher-Educational activity Crisis. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/education/annal/2017/09/the-rural-higher-education-crunch/541188/

- Maslow, A. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), pp. 370–396.

- McDonald, Michael, United States Elections Project, http://www.electproject.org/home

- Munsey, C. (2008). Why do we vote ?. American Psychological Association.

- Pomante, Michael J.; Schraufnagel, Scot (2015). "Candidate Historic period and Youth Voter Turnout". American Politics Research. 43 (iii): 479–503. doi:10.1177/1532673x14554829. S2CID 156019567.

- Snyder, R. (2011). The impact of age, education, political knowledge and political context on voter turnout. UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, And Capstones.

- Struyk, R. (2017). The Democratic Party has an historic period problem. CNN. [online] Bachelor at: https://www.cnn.com/2017/x/ten/politics/democrats-historic period-problem/index.html [Accessed June 9, 2018].

- The Economist (2014). Why young people don't vote. [online] Available at: https://www.economist.com/the-economist-explains/2014/10/29/why-young-people-dont-vote [Accessed June 9, 2018].

- Tolbert, Caroline J.; Smith, Daniel A. (2005). "The Educative Effects of Ballot Initiatives on Voter Turnout". American Politics Research. 33 (2): 283–309. doi:10.1177/1532673x04271904. S2CID 154470262.

External links [edit]

- "National Turnout Rates, 1787-2018" (United States Election Projection)

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Voter_turnout_in_United_States_presidential_elections

0 Response to "what percent of americans are registered to vote"

Post a Comment